Introduction

Specifically designed cognitive behavioural principles are adopted in the management of obesity with a view to improving patients’ long-term adherence to the changes in their eating and exercising habits. Originally, the treatment was based on learning theory (i.e., behaviourism), which postulates that the behaviours directly leading obesity (overeating and under-exercising) are predominantly learned, and can therefore be modified or relearned by associating re-education strategies with procedures designed to modify environmental cues (antecedents) and reinforce ‘good’ behaviour (consequences) [1]. However, since our understanding of the root causes of obesity has progressed, this approach to treatment has seen the integration of procedures derived from social cognitive theory [2] and cognitive therapy [3], as well as specific recommendations on diet and exercise. This complex combination is now known as “weight loss lifestyle modification” [4], and here we describe the principal components, the short and long-term outcomes, and recent developments in such treatment programs.

Delivery of weight-loss lifestyle-modification programs

Losing weight is only half the story, and so weight loss lifestyle modification programs are designed to feature both a weight loss phase, consisting of 16–24 weekly sessions over a 6-month period, followed by phase targeted to weight maintenance. While there is general agreement about the length of the first phase – after 6 months weight loss tends to reach a plateau – no definitive data is yet available about the optimal duration and intensity of the weight maintenance phase [5].

The literature to date mainly derives from clinical research settings, in which the treatment has been tested in individual sessions, in groups sessions comprising ~10-20 participants, and in various combinations of the two. In the real world, however, weight loss lifestyle modification programs are delivered in various clinical environments, including primary care, private dietetics practices, inpatient rehabilitation units, and commercial clinics. Although the treatment can be delivered by a variety of professional figures, such as physicians, dieticians, physiotherapists and psychologists trained in cognitive behavioural therapy for obesity, known as “lifestyle modification counsellors”, a multidisciplinary lifestyle modification team is best placed to manage the complex clinical problems often associated with obesity [5]. In these multidisciplinary teams, the physicians assess the patients, manage any medical complications, engage the patient in the treatment, and conduct periodic medical check-ups, and the other aspects of lifestyle modification are handled by the relevant experts in a fully orchestrated approach.

Lifestyle modification program components

Standard lifestyle modification programs have three main components: (i) dietary recommendations, (ii) physical activity recommendations, and, last but by no means least, (iii) cognitive behavioural therapy to address weight loss and weight maintenance obstacles [4] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The three components of weight loss lifestyle modification programmes

Dietary recommendations

Weight loss lifestyle modification programs recommend a low-fat, (relatively) high-carbohydrate, low-calorie diet aimed at inducing a calorie deficit of 500–1,000 kcal/day. This should produce a mean weight loss of 0.5–1.0 kg/week, and eventually reduce cardiovascular risk markers [6]. Unfortunately, the main obstacle to reaching these goals is the patients themselves, and adherence is often an issue. However, empowering patients by training them to count their own calorie intake, with the aid of a purpose-designed booklet, can go some way to improving adherence, as can increasing dietary structuralization and limiting food choices. Providing comprehensive meal plans, including grocery lists, menus and recipes, helps to provide structure to the diet, and restricting the choice of food will reduce temptation and the opportunity to miscalculate energy intake [4]. The effectiveness of this strategy is supported by a study showing that the provision of both low-calorie food (free of charge or subsidized) and structured meal plans resulted in significantly greater weight loss than a diet with no additional structuralization [7]. Another useful strategy for increasing diet adherence is meal replacement, as confirmed by a meta-analysis of six RCTs, which showed patients given liquid meal replacements lost 3 kg more on average than those on a conventional diet [8]. Finally, a similarly effective strategy for facilitating dietary adherence and weight loss is the use of portion-controlled servings of conventional foods [9].

Physical activity recommendations

The goal of lifestyle modification programs is to help patients gradually achieve a level of physical activity sufficient to produce a calorie deficit of at least 400 kcal/day [10]. Patients are encouraged to check their baseline number of steps using a pedometer, and then to add 500 steps at 3-day intervals up to a target value of 10,000-12,000 steps/day. Jogging (20–40 min/day), cycling or swimming (45–60 min/day) may replace walking. Unlike diet adherence, exercise adherence tends to increase the less structure is imposed, presumably through a reduction in the barriers to exercising (e.g., lack of time or financial resources) [4]. This is supported by several studies, for example one showing that patients tend to engage in more physical activity if instructed to do so on their own at home than if asked to attend on-site, supervised, group-based exercise sessions [11]. Interestingly, it has also been reported that increasing lifestyle activity (e.g., using stairs rather than elevators, walking rather than riding the bus or driving, and reducing the use of labour-saving devices) can produce comparable weight loss to structured exercise programs, but greater weight maintenance over time [12]. It may also be helpful to suggest multiple short sessions of exercise (of 10 minutes each), as opposed to long workouts, an approach that seems to help patients accumulate more minutes of daily exercise [13].

Cognitive behavioural therapy

The cognitive behavioural therapy component of lifestyle modification programs is based upon a set of procedures, which have been described in several recent reviews [4,5,14], aimed at addressing both weight loss and weight maintenance obstacles (see Table 1).

Table 1. Main cognitive behavioural procedures of weight lost lifestyle modification programmes

Procedures for addressing weight loss obstacles

- Self-monitoring

- Goal setting

- Stimulus control

- Practising alternative behaviours

- Proactive problem solving

- Cognitive restructuring Involving significant others

Procedures for addressing weight maintenance obstacles

- Providing continuous care

- Encouraging patients to work on weight maintenance instead of weight loss

- Establishing weight maintenance range and long-term self-monitoring

- Building the long-term weight control mindset

- Discontinuing self-monitoring

- Devising a contingency plan

- Building a weight maintenance plan

One of the main problems with traditional weight loss lifestyle modification programs delivered in group sessions is that they are essentially a series of pre-packaged lessons in which the clinicians teach all patients all the procedures involved in the program. The lessons are delivered in the pre-planned order, even if one or more patients have not yet had enough input to overcome their problems, or have failed to understand entirely. These programs therefore more resemble psycho-educational intervention than the cognitive behaviour therapy applied in the treatment of other psychological disorders, in which the approach is highly personalized and the procedures are introduced in such a way as to target the specific processes maintaining a patient’s problems. The most recent developments in weight loss lifestyle modification programs partly have made some steps to personalize delivery by introducing individual sessions with a case manager [15,16], but the set lessons and uniformity of procedures still apply.

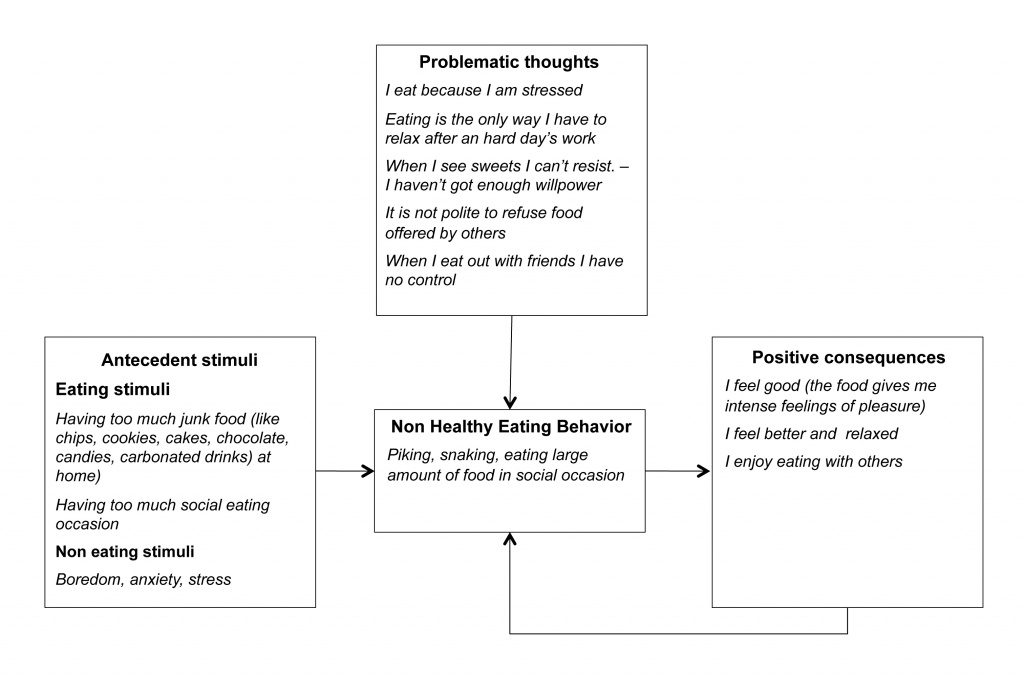

The Villa Garda Lifestyle Modification Program [5], on the other hand, has been designed to maximize the individualization of such treatment, and is delivered in individual sessions that follow a structure similar to that of cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders (i.e., in-session weighing, reviewing self-monitoring, setting the agenda collaboratively, working through the agenda, setting homework, summarizing the session, and arranging the next appointment). The program also benefits from the introduction of the personal “cognitive behavioural formulation”, a procedural tool specifically designed to further individualize the treatment. The formulation, widely used in other areas of cognitive behavioural therapy [17], but not in standard weight loss lifestyle modification programs, is a visual representation (a diagram) of the main cognitive behavioural processes that are hindering adhesion to weight loss and lifestyle change in that particular patient. Led by the clinician, but with the active involvement of the patient, the formulation is constructed step by step, without haste. A natural first step in this process is to elicit from the patient which, if any, stimuli associated with eating (i.e., the sight of food, social eating situations) and/or not (i.e., life events and changes of mood) influence their eating behaviour. The clinician can then assess whether overeating is maintained by any positive emotional and/or physical consequences of food intake, and/or bring to light any problematic thoughts (see Figure 2). In this way the formulation helps the clinician to select the specific procedures most likely to help the patient and to implement a targeted, fully individualized treatment. Once the formulation has been drawn up, the clinician can discuss its implications with the patient, emphasizing that control of eating is not wholly dependent on their willpower, but can be improved through specific strategies designed to counteract the processes hampering adhesion to the eating changes necessary to lose weight. The clinician should also stress that the formulation is provisional and will be custom-modified as needed during the course of the treatment.

Figure 2. An example of personal cognitive behavioural formulation, featuring a patient’s main obstacles to weight loss (based on this formulation, the treatment was focused on reducing eating stimuli; addressing boredom, anxiety, and stress; challenging problematic thoughts; and finding alternatives to food as a reward

Outcomes of weight loss lifestyle modification programs

A recent systematic review on the outcome of weight loss lifestyle modification programs found that at 1 year, about 30% of participants had a weight loss of ≥10%, 25% of between 5% and 9.9%, and 40% of ≤4.9% [18]. As mentioned, weight loss reaches its peak after six months of treatment, and in the absence of a weight maintenance programs the trend starts to reverse, with half of patients returning to their original weight after about five years [19]. However, trials of the latest incarnations of weight loss lifestyle modification programs that include the most innovative and powerful procedures have shown better long-term results. The most striking example is the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study, which assessed the effects of intentional weight loss on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in 5,145 overweight/obese adults with type 2 diabetes, randomly assigned to intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) or usual care (i.e., diabetes support and education – DSE). At year eight, 88% of both groups completed an outcomes assessment, which revealed that ILI and DSE participants lost, on average, 4.7% and 2.1% of their initial weight, respectively (P < 0.001). 50.3% and 35.7% respectively lost ≥5% (P < 0.001), and 26.9% and 17.2% respectively lost ≥10% (P < 0.001) [20]. These impressive figures show that well conducted lifestyle modification programs can produce clinically meaningful weight loss long-term.

New avenues

In recent years, major efforts have been devoted to improving weight loss lifestyle modification program outcomes by integrating pharmacotherapy, residential treatment and/or bariatric surgery.

Combining weight loss lifestyle modification with pharmacotherapy

One of the main factors implicated in the long-term failure of weight maintenance is the biological pressure to regain weight. Pharmacological therapies may be able to alleviate this pressure, and it is therefore vital to consider their integration into weight loss lifestyle modification programs. The most significant study on this issue to date is a randomized controlled trial that compared the effects of group-based weight loss lifestyle modification and sibutramine (15 mg/day), alone or in combination. This revealed that, after one year, participants treated with the combined approach lost nearly twice as much weight as those receiving either therapy alone [21]. Unfortunately, sibutramine has now been taken off the market due to an unfavourable safety record in individuals with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases or diabetes mellitus. Nonetheless, the availability of new weight-loss drugs (i.e., lorcaserin hydrochloride, or a combination of phentermine and extended-release topiramate), recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, may prove effective in combination with lifestyle modification in the management of obese patients.

Combining lifestyle modification with inpatient rehabilitation

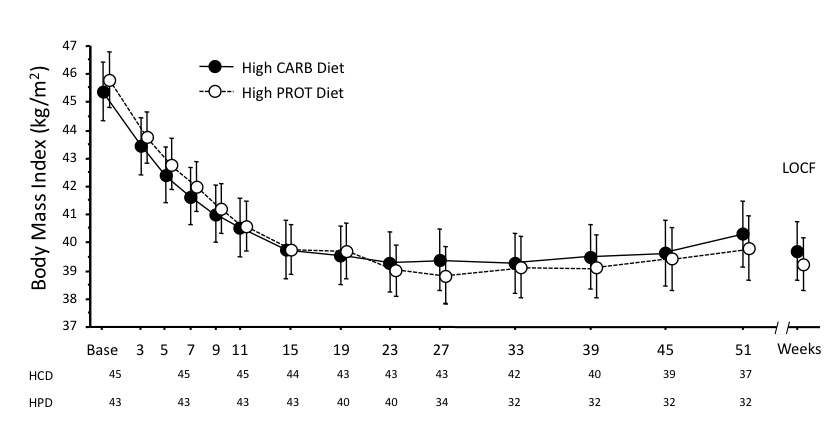

Inpatient rehabilitation treatment has been developed in Italy to manage patients with morbid obesity and severe comorbidities and/or disability who do not respond to standard outpatient treatment. A recent randomized controlled trial assessed the effect on 88 morbidly obese patients of high-protein (HPD) and high-carbohydrate diets (HCD), of identical energy content and percentage fat and saturated fat, combined with individualized weight loss cognitive behavioural procedures based on the principles described in this chapter [22]. The treatment was divided into two stages: Stage One (inpatient treatment; 3 weeks) comprising 15 group cognitive behavioural sessions (5 per week), regular scheduled aerobic exercise, and 6 physiotherapist-led calisthenics sessions; and Stage Two (outpatient treatment; 40 weeks) comprising 12 individual sessions of 45 minutes each with a dietician trained in lifestyle modification, held over a period of 40 weeks. In completers (N=69), weight loss was 15.0% for HPD and 13.3% for HCD at 43 weeks, with no significant difference between the arms observed throughout the study period (Figure 3). Both diets also produced a similar improvement in cardiovascular risk factors and psychological profiles. The percentage weight loss achieved by these treatments was much higher than the mean 8–10% seen in conventional lifestyle modification programs, and, furthermore, no tendency to regain weight was observed between months 6 to 12. These findings indicate that inpatient rehabilitation treatment followed by individual outpatient sessions can increase the positive effect of lifestyle modification on weight loss and maintenance.

Figure 3. An example of personal cognitive behavioural formulation, featuring a patient’s main obstacles to weight loss (based on this formulation, the treatment was focused on reducing eating stimuli; addressing boredom, anxiety, and stress; challenging problematic thoughts; and finding alternatives to food as a reward)

Combining lifestyle modification with bariatric surgery

Bariatric surgery makes no claims to modify a patient’s lifestyle, instead achieving weight loss through the biological alteration of gastrointestinal function, hence long-term maintenance is by no means guaranteed. However, it is likely that combining bariatric surgery with a weight loss lifestyle modification program may improve the patient outcomes. Confirmation of this hypothesis comes from a trial of 144 Hispanic Americans randomized, 6 months after gastric bypass surgery, to comprehensive nutrition and lifestyle educational intervention (n=72) or not (n=72) [23]. 12 months after the surgery, both groups had lost significant weight, but those who also received weight loss lifestyle modification showed greater excess weight loss (80% vs. 64% of preoperative excess weight; P<0.001), and were significantly more involved in physical activity than comparison group participants. Another study randomized 60 consecutive morbidly obese patients who had undergone gastric bypass surgery into low-exercise or multiple-exercise groups, finding that the latter patients had a significantly more rapid reduction of body mass index, excess weight loss and fat mass compared with the former [24]. As a whole, these findings indicate that bariatric surgery may be more effective if integrated in a broader strategy of obesity management including education and lifestyle modification.

Conclusions

Lifestyle modification is the cornerstone of obesity management. Programs based on lifestyle modification have been dramatically improved over recent years, and we now have data proving their efficacy in producing long-term weight loss. Very promising results have been achieved by individualizing the treatment, and integrating innovative cognitive behavioural procedures. Recent data also show that weight loss outcomes are improved when pharmacotherapy, inpatient treatment, and bariatric surgery are combined with lifestyle modification, indicating that such programs should be at the forefront of an individualized multidisciplinary treatment for obesity.

References

- Stuart RR (1967) Behavioral control of overeating. Behav Res Ther 5:357-365.

- Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G (1979) Cognitive Therapy of Depression: A Treatment Manual. Guilford Press, New York

- Fabricatore AN (2007) Behavior therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy of obesity: is there a difference? J Am Diet Assoc 107:92-99.

- Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, El Ghoch M (2013) Lifestyle modification in the management of obesity: achievements and challenges. Eat Weight Disorder: 18:339-49.

- Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults-The Evidence Report. National Institutes of Health (1998). Obes Res 6 Suppl 2:51S-209S.

- Wing RR, Jeffery RW, Burton LR, Thorson C, Sperber-Nissimoff K, Baxter JE (1996) Food provision vs. structured meal plans in the behavioral treatment of obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 20:56-62.

- Heymsfield SB, van Mierlo CA, van der Knaap HC, Heo M, Frier HI (2003) Weight management using a meal replacement strategy: meta and pooling analysis from six studies. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 27:537-549.

- Metz JA, Stern JS, Kris-Etherton P, Reusser ME, Morris CD, Hatton DC, Oparil S, Haynes RB, Resnick LM, Pi-Sunyer FX, Clark S, Chester L, McMahon M, Snyder GW, McCarron DA (2000) A randomized trial of improved weight loss with a prepared meal plan in overweight and obese patients: impact on cardiovascular risk reduction. Arch Intern Med 160:2150-2158.

- Dalle Grave R, Centis E, Marzocchi R, El Ghoch M, G. M (2013) Major factors for facilitating change in behavioural strategies to reduce obesity. Psychol Res Behav Manag 6:101-110

- Perri MG, Martin AD, Leermakers EA, Sears SF, Notelovitz M (1997) Effects of group- versus home-based exercise in the treatment of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol 65:278-285.

- Andersen RE, Wadden TA, Bartlett SJ, Zemel B, Verde TJ, Franckowiak SC (1999) Effects of lifestyle activity vs structured aerobic exercise in obese women: a randomized trial. Jama 281:335-340.

- Jakicic JM, Wing RR, Butler BA, Robertson RJ (1995) Prescribing exercise in multiple short bouts versus one continuous bout: effects on adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, and weight loss in overweight women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 19:893-901.

- Wadden TA, Webb VL, Moran CH, Bailer BA (2012) Lifestyle modification for obesity: new developments in diet, physical activity, and behavior therapy. Circulation 125:1157-1170.

- The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention (2002). Diabetes Care 25:2165-2171.

- Ryan DH, Espeland MA, Foster GD, Haffner SM, Hubbard VS, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Knowler WC, Yanovski SZ (2003) Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials 24:610-628.

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Shafran R, Bohn K, Hawker DM, Murphy R, Straebler S (2008) Enhanced cognitive behavior therapy for eating disorders: The core protocol. In: Fairburn CG (ed) Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. Guilford Press, New York, pp 45-193

- Christian JG, Tsai AG, Bessesen DH (2010) Interpreting weight losses from lifestyle modification trials: using categorical data. Int J Obes 34:207-209.

- Wing RR (2002) Behavioral weight control. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ (eds) Handbook of Obesity Treatment. The Guildford Press, New York, pp 301-316

- Eight-year weight losses with an intensive lifestyle intervention: the look AHEAD study (2014). Obesity 22:5-13.

- Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, Sarwer DB, Phelan S, Cato RK, Hesson LA, Osei SY, Kaplan R, Stunkard AJ (2005) Randomized Trial of Lifestyle Modification and Pharmacotherapy for Obesity. N Engl J Med 353:2111-2120.

- Dalle Grave R, Calugi S, Gavasso I, El Ghoch M, Marchesini G (2013) A randomized trial of energy-restricted high-protein versus high-carbohydrate, low-fat diet in morbid obesity. Obesity 21:1774-1781.

- Nijamkin MP, Campa A, Sosa J, Baum M, Himburg S, Johnson P (2012) Comprehensive nutrition and lifestyle education improves weight loss and physical activity in Hispanic Americans following gastric bypass surgery: a randomized controlled trial. J Acad Nutr Diet 112:382-390.

- Shang E, Hasenberg T (2010) Aerobic endurance training improves weight loss, body composition, and co-morbidities in patients after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 6:260-266.